The memory hierarchy why your CPU needs three different types of short-term memory. Modern processors are almost too fast for their own good. A high-end CPU core operates at roughly 4GHz to 5GHz, meaning it can execute billions of cycles per second. Main system memory (RAM), however, cannot keep up with that pace.

If a CPU had to fetch data directly from RAM for every single instruction, it would spend the vast majority of its time idle, waiting for data to arrive. This creates the Von Neumann Bottleneck.

To solve this, computer architects don’t just use memory; they use a hierarchy of tiered storage layers Registers, Cache, and RAM each designed to balance three competing constraints: data latency, physical density, and cost.

For computer science students, hardware enthusiasts, and system architects, understanding the specific differences between Ram, Cache, and Registers is fundamental.

Read our complete guide on computer hardware.

The Physical Difference: SRAM vs. DRAM

The most common confusion regarding memory is why we don’t simply build a computer with 32GB of the fastest available memory (Registers) and ditch the slower RAM entirely.

The answer lies in the physics of how bits are stored.

Registers and Cache use SRAM (Static Random Access Memory).

SRAM stores data using flip-flop circuits, typically requiring 6 transistors per bit. It is incredibly fast and stable it doesn’t need to be refreshed to keep its data. However, because it requires 6 transistors for a single bit, it takes up a massive amount of physical space on the silicon die.

Learn also: location of active CPU computations

RAM uses DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory).

DRAM stores data using capacitors. It is much simpler, requiring only 1 transistor and 1 capacitor per bit. This allows engineers to pack billions of bits into a small chip (high density). However, capacitors leak charge. They must be electronically “refreshed” thousands of times per second, which creates latency and overhead.

The Engineering Constraint:

If you tried to build 32GB of storage using the 6-transistor SRAM found in registers, the chip would be the size of a pizza box, cost thousands of dollars, and generate enough heat to melt through your motherboard. We use DRAM for main memory not because we want to, but because it is the only way to get gigabytes of capacity at a viable size and price.

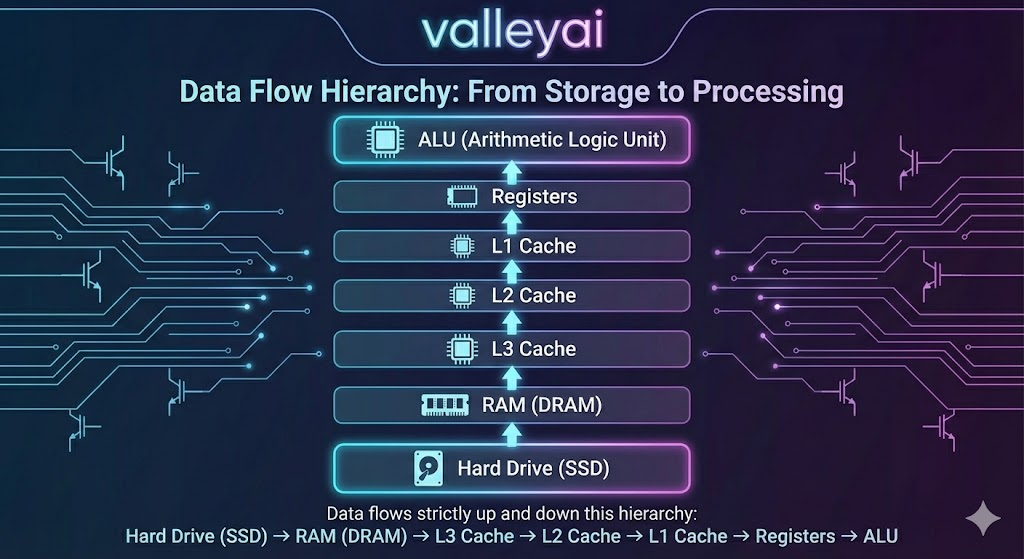

The Data Journey: A Supply Chain of Information

To understand the practical difference between ram cache and registers, we need to look at the lifecycle of a single instruction. Imagine a CPU executing a line of code that adds two numbers.

RAM (The Staging Area):

The Operating System loads the entire program and its data from the SSD into RAM. RAM is large enough to hold the full context of the application, but it is far away from the CPU core in terms of clock cycles. Fetching data from here takes roughly 100 nanoseconds. To a 4GHz CPU, that is an eternity.

Cache (The Prediction Layer):

The CPU’s hardware logic anticipates what data the processor will likely need next (based on locality algorithms) and pulls a copy of it from RAM into the Cache.

- L3 Cache: Shared by all cores. Large but slightly slower.

- L2 Cache: Dedicated to a specific core.

- L1 Cache: Extremely small, integrated directly next to the execution units. Accessing L1 cache takes only 1 to 3 clock cycles.

Registers (The Workbench):

This is the destination. Before the CPU can actually add those two numbers, the data must be moved from the Cache into the Registers. Registers are the only memory the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) can work with directly. They hold the immediate operands (the actual numbers being added) and the result. Access is instantaneous (0-1 clock cycle).

Detailed Comparison by Function

Lets breakdown the difference between ram cache and registers.

Registers: The Architect’s Tools

Registers are the fastest, smallest, and most expensive memory in the system. They are located inside the CPU core itself.

- Capacity: Measured in bits. A 64-bit processor has general-purpose registers that are 64 bits wide. The total volume of register space is minuscule (often less than a few kilobytes).

- Control: Compiler-Controlled. When code is compiled from C++ or Rust into Assembly, the compiler explicitly decides which variables go into which registers. The programmer (or their compiler) has direct control here.

- Role: They hold the active state of the CPU the instruction pointer, the stack pointer, and the variables currently being mathematically manipulated.

Cache: The Invisible Bridge

Cache is designed to hide the latency of RAM. It works automatically; you cannot write code that says save this variable to L1 Cache.

- Capacity: Measured in Kilobytes (L1/L2) to Megabytes (L3).

- Control: Hardware-Controlled. The CPU has dedicated circuits that manage cache lines. If the CPU asks for data and it’s found in the cache, it’s a cache hit. If not, it’s a cache miss, and the system must stall while fetching from RAM.

- Role: It acts as a buffer. Because programs tend to access memory sequentially, the cache grabs blocks of data (cache lines) anticipating they will be used soon.

RAM: The System Workspace

RAM is the primary workspace for the Operating System.

- Capacity: Measured in Gigabytes (8GB, 16GB, 64GB).

- Control: OS-Controlled. The Operating System determines which programs get memory addresses in RAM.

- Role: It provides the volume needed to keep applications open and responsive, preventing the system from having to read from the incredibly slow SSD/Hard Drive.

The Locality Secret: Why Cache Actually Works

The hierarchy relies on a principle called Locality of Reference. Without this, the cache would be useless.

- Spatial Locality: If a program accesses memory address

100, it is highly likely to access address101next. (Think of reading an array or a list sequentially). The cache loads100through128automatically, so the next requests are instant. - Temporal Locality: If a program uses a variable

xnow, it will likely usexagain very soon (think of a loop counter). The cache keeps recently used data ready for reuse.

Because code is generally predictable, a small amount of Cache (e.g., 32MB) can successfully serve the CPU’s needs 95% of the time, making the slow RAM feel much faster than it actually is.

Comparison Table: RAM vs Cache vs Registers

| Feature | Registers | Cache Memory (L1/L2/L3) | RAM (Main Memory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Flip-Flops (Logic Gates) | SRAM (Static RAM) | DRAM (Dynamic RAM) |

| Location | Inside CPU Core (ALU) | On CPU Die | Motherboard DIMM Slots |

| Latency | ~0-1 Clock Cycle | ~3 – 50 Clock Cycles | ~200+ Clock Cycles |

| Size/Capacity | Bits to Bytes (e.g., 64-bit) | Megabytes (e.g., 32MB) | Gigabytes (e.g., 32GB) |

| Managed By | Compiler / Hardware | Hardware (Cache Controller) | Operating System / MMU |

| Speed | Fastest | Very Fast | Slow (Relative to CPU) |

| Cost per GB | Extremely High | High | Low |

Future Outlook: Blurring the Lines

The rigid distinction between these layers is beginning to evolve. Technologies like AMD 3D V-Cache stack extra SRAM vertically on top of the processor to create massive L3 caches, significantly reducing the need to access RAM in gaming workloads. Meanwhile, Apple Unified Memory Architecture places the DRAM on the same package as the CPU, reducing the physical distance and latency penalties traditionally associated with main memory.

While the technologies improve, the fundamental logic remains: we will always need a small amount of ultra-fast storage for immediate work (Registers) and a large amount of slower storage for capacity (RAM).

FAQs:

What is the physical location of registers and cache?

Registers are physically embedded inside the CPU execution cores (often next to the ALU). L1 and L2 Cache are also inside the core. L3 Cache is usually shared between cores on the CPU die. RAM is located on separate modules (sticks) plugged into the motherboard, communicating via the Memory Controller Hub.

Is register faster than cache memory?

Yes, absolutely. Registers are the fastest form of memory in a computer. Accessing a register usually takes less than one CPU clock cycle. Even the fastest L1 Cache takes 3-5 cycles. Registers operate at the full speed of the CPU frequency.

Why do we need cache if we have registers?

Density and Cost. Registers are built using Flip-Flops, which are physically large and power-hungry. If we tried to build 32GB of memory using Flip-Flops (Registers), the CPU would be the size of a dinner table and cost millions. We use Cache and RAM as a compromise between speed, size, and cost.

How does cache locality affect program speed?

Cache locality affects speed by maximizing Cache Hits and minimizing Cache Misses. When a program accesses memory sequentially (good spatial locality), the CPU finds the data in the L1/L2 cache rather than waiting hundreds of cycles to fetch it from RAM. Poor locality causes the CPU to stall (stop working) while waiting for data.

Is RAM more important than CPU cache for gaming?

For smoothness (1% low FPS), CPU Cache (specifically 3D V-Cache or large L3) is often more important. Large L3 cache keeps complex game physics and geometry data close to the core, preventing stutter. However, you need enough RAM (capacity) to hold the game assets. If you run out of RAM, the system swaps to the SSD, which destroys performance.

High Cache: Higher max FPS, less stutter.

High RAM Capacity: Prevents crashes and massive lag spikes.

Is RAM faster than cache?

No. RAM is significantly slower than cache.

SRAM (Cache): Does not need refreshing; integrated on the CPU die.

DRAM (RAM): Needs refreshing; located inches away from the CPU.

What is the difference between CPU cache and RAM?

The main difference is volatility technology and proximity. Cache uses SRAM (fast, complex, on-chip) to store frequently used data. RAM uses DRAM (slower, dense, off-chip) to store the bulk of running program data.

Can I upgrade my CPU Cache?

No. L1, L2, and L3 cache are soldered directly onto the CPU die. To get more cache, you must buy a different CPU (e.g., upgrading to an AMD X3D model or an Intel Extreme edition).

Do registers store instructions or data?

Both. There are General Purpose Registers (GPR) for data (like integers) and Special Purpose Registers (like the Instruction Pointer or Program Counter) that track which line of code acts next.

What happens if Cache is full?

The Cache Controller uses an eviction policy, typically LRU (Least Recently Used). It looks at the data that hasn’t been touched in a while, writes it back to RAM (if modified), and deletes it from the Cache to make room for new data.

Recommended Next Steps For Learning

- Deep Dive: Look up Cache Miss Penalty to understand how code inefficiency slows down CPUs.

- Related Topic: Explore Virtual Memory to see how the OS uses the Hard Drive to fake having more RAM.

- Hardware Focus: Research HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) to see how GPUs handle this hierarchy differently than CPUs.

Kaleem

My name is Kaleem and i am a computer science graduate with 5+ years of experience in Computer science, AI, tech, and web innovation. I founded ValleyAI.net to simplify AI, internet, and computer topics also focus on building useful utility tools. My clear, hands-on content is trusted by 5K+ monthly readers worldwide.